What's Hot: Did January Mark The Bottom For The DC-Area Housing Market? | The Roller Coaster Development Scene In Tenleytown and AU Park

St. Elizabeth's Architecture Through the Ages

St. Elizabeth's Architecture Through the Ages

✉️ Want to forward this article? Click here.

The Center Building at St. Elizabeths. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The National Building Museum debuted a new exhibit this past weekend which explores the establishment and evolution of the St. Elizabeth’s medical campus, a 350-acre site in Congress Heights. The site has been walled off from the rest of the city for over 150 years and has been largely vacant for over a decade. Now, as it is on the verge of a large-scale, comprehensive redevelopment, this exhibit revisits the campus’ history.

While the land where St. Elizabeth’s sits was originally occupied by the Piscatawny tribes, the British government deeded it to John Charman in the 1660s, who dubbed the site “St. Elizabeths”. After changing hands several times, prominent local landowner Thomas Blagden (for whom Blagden Alley is named) acquired 185 acres of the site in the 1840s.

Around the same time, the moral reform movement was going strong and seeking to address societal ills like disease, crime and violence by offering people the opportunity to have a better quality of life. The Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane (AMSAII; later renamed the American Psychiatric Association) was established in 1844 and began issuing recommendations for how to care for the mentally ill, championing fresh air and ample outdoor recreation space.

The federal government took note of this shift and Congress authorized the creation of the “Government Hospital for the Insane” in 1852. The St. Elizabeths site was one of the largest tracts of farmland in the city and was a prime piece of land overlooking DC and both the Anacostia and Potomac Rivers. To secure the site, influential advocate Dorothea Dix persuaded Blagden and his wife to sell their portion of the land to the federal government; they parted with it for $25,000.

“Old Original Farmhouse” owned by the Blagdens. National Archives and Records Administration.

The inaugural Center Building of the Government Hospital for the Insane was completed in 1855; Congress officially renamed the campus St. Elizabeth’s in 1916, a moniker that staff and residents had been using colloquially for decades by that time. The campus was completely self-sufficient for a long time, with the nearly-200 acre East Campus used to grow food and crops for the hospital prior to 1904.

Dr. Thomas Kirkbride, a founding member of the AMSAII, became the namesake for the first standard of asylum architecture, which was on display at St. Elizabeth’s. The concept of Kirkbride buildings revolves around “Moral Treatment”, where buildings have a large central core flanked with angled, stepped-back wings, creating one-person rooms clustered according to affliction and enjoying ventilation and unobstructed views; however, the structures had poor living conditions and were overcrowded in practice.

The Center Building adheres to the Kirkbride style, although the design was heavily influenced by then-Superintendent Dr. Charles Nichols, whose apartment and administrative offices were located in the building’s core. Nichols submitted his own sketches to the architect, asserting that the structure should “blend architectural beauty with practical convenience and utility”. Behind the Center Building were segregated East and West Lodges “for the colored insane”, smaller, open dormitories without separation by ailment which did not follow the Kirkbride plan.

Some affluent patients, such as Sarah Burroughs, were housed in cottages on campus with their own personal nursing staff. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, c. 1890s

In 1866, the AMSAII recommended a “Cottage Plan” for housing, suggesting that small, specialized home-like structures were more conducive to effectively treating the mentally ill than the Kirkbride style. The first Cottage Plan addition to the campus was Atkins Hall in 1878, followed in the 1880s by Burroughs Cottage, which hosted affluent, paying patients. These and other cottages were scattered about, not constructed with any formal plan for placement. This was a major period of expansion for the campus, with Boston architectural firm Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge winning the rights to construct 15 new buildings in 1900. These “letter buildings” (Buildings A, B, C etc.) conformed to a single design aesthetic and added 1,000 patient beds; this phase also produced Hitchcock Hall, a performance venue for patients.

The campus expanded further from 1910-1940, with the addition of several tiled roof, red-brick-and-limestone buildings in the City Beautiful-style east of Nichols Avenue. In response to the prevalence of tuberculosis in the early 20th century, five cottages specifically for those suffering from the disease were built by 1914, each with a porch and 20 patients. Many employees also lived in cottages on-campus, as was typical of large institutions created in the 19th century.

The Center Building in 2016. Plans to retain as much of the interior of the Center Building were hampered by the discovery of original building materials and a structural system that were in far worse condition than expected. © Colin Winterbottom

Although the majority of development was completed in the 1940s, newer buildings were added later, including a replacement for Howard Hall and other multi-story buildings focused on outpatient treatment and scientific research.

The federal government began transferring the land of the campus to the District in the 1960s; in 1979, the site was designated a National Historic District. By the 1990s, the majority of the campus was emptying out, creating the question of what to do with the site going forward. In 1991, the site was granted National Historic Landmark status; the city also unveiled the “Rehoboth Village Plan”, a proposal to create a planned, mixed-use community where the mentally ill would live among middle-income households on the West Campus.

Now, after another decade of planning, progress is being made to transform St. Elizabeth’s and its long-vacant, deteriorating structures into a thriving community that is more-integrated with the Congress Heights neighborhood.

Following an extensive renovation by the General Services Administration, the Center Building will be repurposed as offices for the Department of Homeland Security. Courtesy of the U.S. General Services Administration.

The West Campus will be developed into the new headquarters for the Department of Homeland Security. As part of this, the Center Building was gutted in 2016 and will be renovated into government offices, with some of the original door transoms and trim incorporated. The remainder of St. Elizabeth’s East will be developed into a mixed-use community, including a sports entertainment facility and over 1,300 residential units.

The exhibition on St. Elizabeth’s is now open to the public at the National Building Museum.

See other articles related to: congress heights, historic, historic preservation, history, st. elizabeth's

This article originally published at http://dc.urbanturf.production.logicbrush.com/articles/blog/st._elizabeths_architecture_through_the_ages/12369.

Most Popular... This Week • Last 30 Days • Ever

Lincoln-Westmoreland Housing is moving forward with plans to replace an aging Shaw af... read »

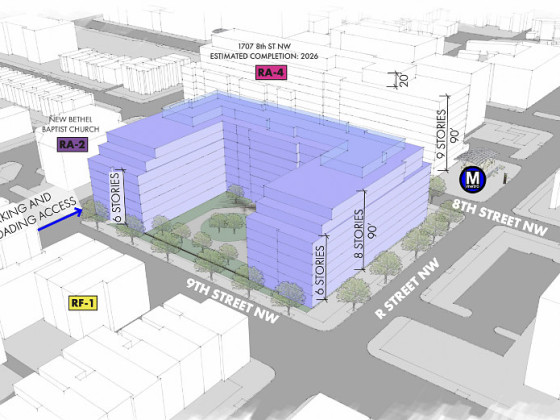

The small handful of projects in the pipeline are either moving full steam ahead, get... read »

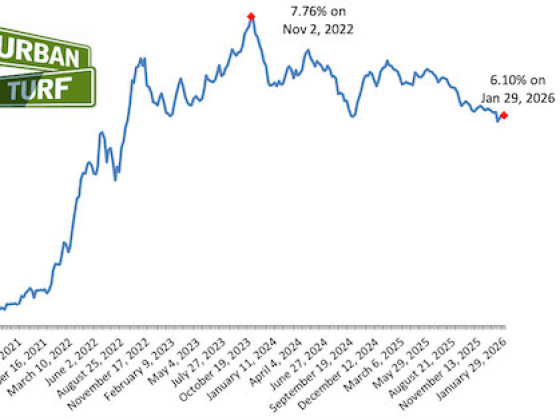

A report out today finds early signs that the spring could be a busy market.... read »

A potential collapse on 14th Street; Zuckerberg pays big in Florida; and how the mark... read »

A potential innovation district in Arlington; an LA coffee chain to DC; and the end o... read »

DC Real Estate Guides

Short guides to navigating the DC-area real estate market

We've collected all our helpful guides for buying, selling and renting in and around Washington, DC in one place. Start browsing below!

First-Timer Primers

Intro guides for first-time home buyers

Unique Spaces

Awesome and unusual real estate from across the DC Metro